CHAPTER VIII

OCCUPATION SECURITY AND INTELLIGENCE MEASURES

Assignment of Responsibilities

Parallel with the establishment and slow growth of Military Government, the operations of certain civil and counter intelligence units and agencies entered into play as an indispensable factor in the tranquil development of the Occupation. As the Occupation progressed, the duties of combating and controlling diverse elements, subversive or inimical to the objectives of the Occupation, which were envisioned in the basic plan for Operation "Blacklist,"1 were expanded immeasurably to cover every facet of the intelligence problem.

Developed before Japan's capitulation2 the Intelligence Annex to "Blacklist" was originally designed to serve only during the initial phase of the Occupation; however, it already contained the essentials later appearing in the second basic document relating to the general intelligence information mission, "Basic Directive for Post-Surrender Military Government in Japan Proper."3

"Blacklist" recognized the "joint character of operational and counter intelligence"4 and further envisaged that:

The surrender of Japan ... will alter the general mission of Counter Intelligence operations. In addition to insuring military security by denying information to the enemy, Counter Intelligence personnel will be confronted with the problem of suppression of organizations, individuals and movements whose existence and continued activities are considered an impediment to the lasting peaceful reconstruction of Japan.5

This paragraph of "Blacklist" clearly characterized the operation of CIS from the beginning of the Occupation to the end.

"Blacklist" specifically identified in a general "wanted list" some of Japan's most dangerous elements, naming particularly the Kempei Tai (Military Police), Tokumu Kikan (Secret Intelligence Service), Kokuryu Kai (Black Dragon Society), Dal Nippon Seijikai (Political Association of Greater Japan), Koku Sui-to (Extreme Nationalist Party), and other extremist organizations, as well as lists of top personnel in the general staff and government.6 It arranged for coordination in the field between counter and operational intelligence staffs in their work of apprehending and interrogating persons on the "wanted lists," and for a central card file on all persons arrested; this coordination also covered the seizure and safeguarding of valuable documents and the interrogation of prisoners and suspects.7

In addition to these specific tasks, the nor-

[231]

mal responsibilities of counter intelligence regarding enemy espionage, sabotage, and subversive activities continued in force, and intensive security education programs to alert troops in vigilance (especially necessary in enemy territory) were instituted.8

The civil censorship responsibilities outlined in "Blacklist" called for centralization of the technical direction and control at theater level. This control was to be exercised with the primary objective of promoting military security and the peaceful future of the country, for action by appropriate agencies and regulation of communications and information media.9

A general SCAP memorandum10 defined certain responsibilities: criminal and police agencies were to be purged of undesirable elements; prisoners held solely under abrogated laws were to be released; certain Japanese political associations and all military and civilian ultra-nationalistic, terroristic, and secret patriotic associations and their affiliates or agencies were ordered dissolved; military training was banned; foreign nationals were required to identify themselves and be registered. CIS was instructed to place under protective custody diplomatic and consular officials of countries, except Japan, which had been at war with any of the United Nations, as well as to hold those civilians from neutral countries or United Nations nationals (resident or interned in Japan) who had participated in the war against the United Nations. The instructions also contained provisions to intern certain categories of Japanese who had played active and dominant roles in the formation of Japan's program of aggression and to hold suspected war criminals incommunicado without distinction as to rank or position; Japanese and Korean collaborators were to be removed from positions of responsibility as rapidly as possible. CIS was further directed to establish censorship of civil communications and to preserve certain governmental and civil records.

Basic Plan for Civil Censorship

The Basic Plan for Civil Censorship as formulated before Japan's surrender called for censorship control of Japan under military invasion conditions.11 This outline was subsequently modified by "Blacklist" which delineated the primary objectives of civil censorship under "conditions of peaceful occupation."12 A third plan, the one eventually followed, was adjusted to meet the favorable conditions actually encountered in the first days of the Occupation.13 Under this modification, Civil Censorship in Japan developed into a medium of information on the Japanese military, economic, social, and political activities through control of Japanese communications. It became apparent early that the extent of compliance with terms of the surrender, and the trend of acceptance by the Japanese of Occupation directives could be determined. The Press Section of Civil Censorship was to assist also in the enforcement of the free and factual dissemination of news based upon United Nations standards. Through intelligent eval-

[232]

uation of intercept information, Civil. Censorship would assist in prevention of secret rearmament, the apprehension and conviction of suspected war criminals, the prevention of disorders, the location of Japanese overseas assets, and the recovery of property seized during the war. By control of communications, military security would be maintained as leads developed to expose the existence and activities of underground or other subversive elements and of blackmarket operators.

Evolution of Civil (Occupation) Intelligence

The original CIC mission was defined in orders of long standing

... to assist in maintaining security by detecting and taking countermeasures to nullify enemy intelligence operations, to investigate matters pertaining to espionage, sabotage, treason, sedition, disaffection, and subversive activities occurring within the military establishment, and to make security surveys and assist in the security instruction of military personnel .....14

Upon arrival in Japan, the basic mission was expanded to include detecting conditions inimical to the general objectives of the Occupation, with special emphasis on subversive activities, in addition to current responsibilities of CIC within the military establishment.15

By September 1945 plans for the organization of the Allied Forces which would occupy Japan were completed.

The evolution of civil intelligence, a term adopted in counterdistinction to purely military, strategic theater intelligence, was gradual. The objectives of the Occupation, in its civil aspects, predominated in all missions: gradually, all counter intelligence activities were directed toward that end as surveillance and security operations.16

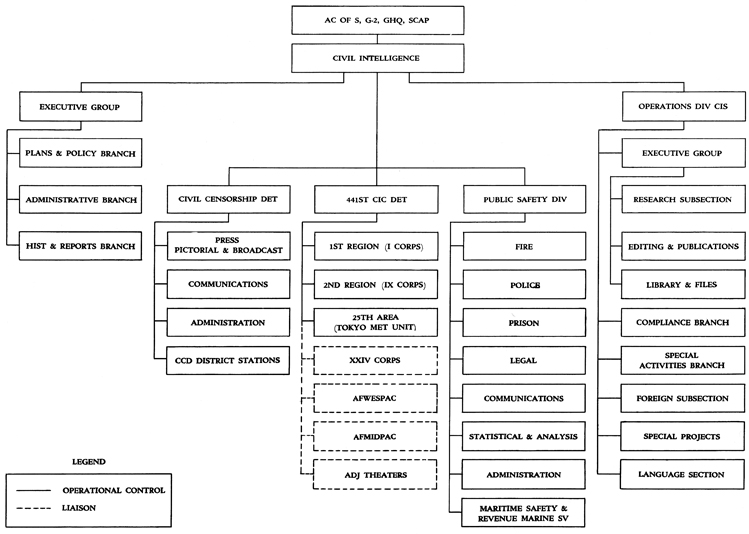

The Civil Intelligence Section played a dual role in the Occupation, as a SCAP Staff Section (CIS) and as an operating agency (Counter Intelligence Division); with its various components, distributed throughout Japan, this agency became a sort of F.B.I. for the Occupation in its special field of security surveillance.17 It functioned in four major components: Operations Branch, the 441st Counter Intelligence Corps, the Civil Censorship Detachment, and the Public Safety Division.18 (Plate No. 75)

The Operations Branch acted as a coordinating staff: evaluation of information gathered from the field by CIC and CCD and the initiating of staff action pertaining thereto were its primary interests. From "research for future operations," the mission of its wartime predecessor, the scope of the division abruptly broadened to one of coordination and action on all aspects of counter intelligence activities.

In the fall of 1945, the apprehension of Japanese war criminal suspects became an immediate and urgent mission. Allied public opinion exerted heavy pressure on Occupation authorities to take prompt action against the war criminals. The responsibility of selecting the priority or "Class A" group, who would be tried before the International Military

[233]

PLATE NO. 75

Organization of Civil (Occupation) Intelligence Division, 15 October 1946

[234]

Tribunal, was a heavy one. Utilizing information developed by intelligence agencies in the Philippines, War Department instructions and new data obtained in Japan, the first list of such persons was compiled on 11 September 1945.19 It was headed by General Hideki Tojo, the premier who led Japan into war, and listed forty men charged with directing the Japanese war effort. The 441st Counter Intelligence Corps was assigned the initial task of apprehending these war criminal suspects; on 13 September 1945, however, the Japanese Government was ordered to turn over to Occupation authorities all of those on the "wanted list." In February 1946 the investigation of war criminals was undertaken by Legal Section, GHQ, SCAP, which became responsible for their prosecution.20 This relieved CIS of further responsibility for Japanese war criminals, although it retained the task of arresting "neutral nationals who actively participated at war against any one of the United Nations." Nevertheless, CIS continued to be interested in those war criminal suspects who were interned through its efforts; their cases were studied and recommendations made for release of those suspects whose arrest was not justified.

An early accomplishment of CIS was the issuance of two important directives which made possible the modification of police laws and agencies through which absolute control over the Japanese people had been maintained.21 Under a series of regulations which were gradually strengthened over the years, especially during the war, the Japanese police exercised virtually unlimited power; their control extended into the fields of economics, drama, press, politics, and religion. Many enforcement groups operated secretly and extreme influence was wielded by the Special Higher Police. There were also the "Thought Police" who, under the "Protection and Surveillance Law for Thought Offense" and partially through use of the "neighborhood associations," attempted to control, supervise and regulate the trends of people's thought and opinion. Their methods were often brutal; they could hold persons for long periods without charges and, by using third degree tactics, they could force confessions to false charges from those who had incurred their disfavor.

SCAP Directives issued 4 and 10 October ordered the elimination of laws permitting such actions and of police agencies which carried them out. They further directed the immediate release of political prisoners and required the removal from office of numerous top police officials, including the chiefs of the metropolitan police departments and of each prefectural police department in Japan; also relieved from office were the Minister of Home Affairs who directed police policy, and the Chief of the Home Ministry Bureau of Police. All these mandates were designed to pave the way for the emergence of a democratic Japan.

One of the first important investigations initiated by CIS in the Occupation concerned the Kempei Tai and Tokumu Kikan, the particular adversaries of counterintelligence agencies during the war. On 4 November the Japanese Government was ordered to submit complete information about these organizations, including lists of all members, organizational charts, descriptions of functions and operations.

[235]

and the policies and laws under which they acted. This was the beginning of comprehensive studies on the two groups, which had been abolished at the beginning of the Occupation concurrently with the demobilization of Japanese armed forces.

From the outset Operations Branch maintained special channels of information which were in direct contact with Japanese sources, and thus often made possible more rapid acquisition of specific data needed for immediate action. Initially, CIS also collected Japanese documents and source material on ultra-nationalistic individuals and organizations which were to be purged; later this activity was extended to include left-wing extremists as well. Dossiers and files were prepared on all foreign nationals resident in Japan, as well as a monthly chart showing the distribution of these persons within the country. Based on these valuable records, recommendations regarding the repatriation of foreign nationals, especially the German groups, became a CIS function, as was the apprehension of non Japanese who assisted in the Japanese war effort, including both neutrals and non-neutrals. Seventy-two persons (among them two Americans) were apprehended in the early days of the Occupation; all were eventually returned to their own countries; some were prosecuted as war criminals.

Approximately 2,000 enemy nationals, whose records were verified by CIS, were removed from Japan in two mass repatriation movements; the majority of these were Germans-former diplomats, interned military and naval personnel, and members of the Nazi party. Their elimination from Japan under Washington policies strengthened the Occupation by reducing security risks.

Civil Censorship Detachment (CCD): Although less sensational in nature, the administration of censorship over Japanese media of public expression offered no less responsibility and no fewer problems than the investigation of war criminals. It was soon evident that close scrutiny of every newspaper, radio script, movie scenario, dramatic production, book, magazine, and pamphlet in Japan would be necessary. The job required inspection not only of the current production of material, but also of that prepared in the years during and before the war. The immediate need, however, was to introduce a code of ethical practice for disseminating organs.22

To establish a permanent criterion, press and radio codes were devised, based on ethical practices in the United States. These were passed on to the Japanese Government in the form of memoranda: the "Press Code for Japan"23, and the "Radio Code for Japan."24 Each followed the directions set forth in the "Freedom of Speech and Press" directive, but also elaborated on several points. One salient stipulation was included in the Press Code "There shall be no destructive criticism of the Allied Forces of Occupation and nothing which might invite mistrust or resentment of those troops." During the early months of the Occupation this and the public tranquility clause were the most frequently violated press rules.

[236]

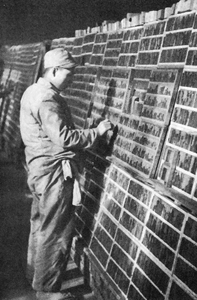

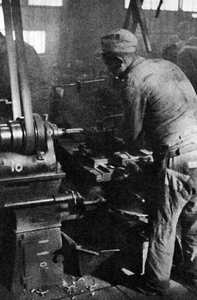

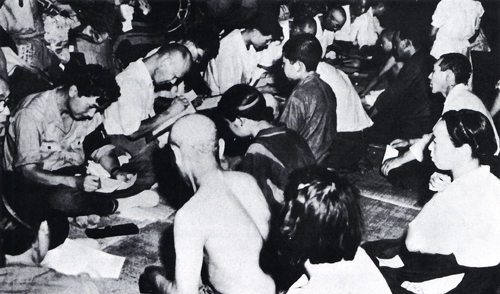

Japanese censor reviews films in Motion Picture Department of

Press, Pictorial, Broadcast Division of CCD, Osaka.

After being read by Japanese nationals, material of interest is referred to the

senior translator who passes on the matter and translates it into English.

PLATE NO. 76

Censorship, July 1947

[237]

As early as 18 September the first case of public reprimand of a newspaper occurred when the Asahi Shimbun was suspended for two days for violating the press code.25 The following day the Nippon Times, Tokyo English language paper, was also suspended for twenty-four hours.26 These suspensions, which were accompanied by explanations of pertinent policy, brought home sharply the standards required by SCAP.

The next step in the direction of establishing free speech and free press in Japan was made by removing government controls from the agencies of public expression. Domei News Agency exercised a monopoly of the news dissemination field, operating under strict censorship of the Board of Information. The Mainichi-Asahi-Yomiurt newspaper combines, also under careful government control, similarly monopolized the newspaper publishing field. A directive of 24 September, prepared by CIS, ordered that:27

In order further to encourage liberal tendencies in Japan and establish free access to the news sources of the world, steps will be taken by the Japanese Government forthwith to eliminate government-created barriers to dissemination of news and to remove itself from direct or indirect control of newspapers and news agencies....

This memorandum further provided that no preferential treatment be accorded to any news distributor. Foreign news agencies were thus permitted to serve the Japanese press. Communications facilities were also made available to newcomers in the field. Aside from that, the existing system of distribution of news in Japan was tolerated under strict censorship "until such time as private enterprise creates acceptable substitutes for the present monopoly." Soon afterward the Domei News Agency was voluntarily abolished.

Another memorandum, "Clarification of Censorship Directive,"28 covered radio news broadcasts, which were restricted to Radio Tokyo. Regulations for the Japanese press handling news regarding the Occupation forces were also stipulated: news items would be usable only if they had been cleared through the GHQ Public Relations Office.

Censorship Advance Detachments were authorized to impound international mail found during their initial surveys and on 13 September the postal division of CCD took over the Japanese postal system, to place communications in every prefecture under Occupation scrutiny.29

Shortly thereafter pre-publication censorship of all major Tokyo newspapers and magazines and Japanese news agency dispatches was initiated; censorship detachments in the field began surveys of post offices, mail channels, press, drama, and radio organizations, and control was placed over telecommunication outlets from Japan. Four district censorship stations had been installed by the end of 1945.30

Examination of internal communications became immediately one of the most direct and reliable "intelligence" sources. Through this medium, leads were developed in practically all cases against major blackmarket operations. In the pictorial field there were sporadic attempts by foreign nations to distribute motion pictures that were likely to stir

[238]

up public unrest. In the broadcast or relay of certain foreign news services, there was a positive field of publicizing racial hatreds, foreign ideologies, and anti-American, anti-Occupation attacks which required constant supervision. The enormous volume of internal mail and telegrams checked by CCD constituted a strong security measure;31 for example, intercepts of foreign subversive propaganda being mailed into Japan from Hong Kong ran as high as 295 pounds in one week.

Examples of security coverage can be found in a continuous flow of information in the form of "spot intelligence reports" on public rallies, formations, plans and programs of organizations bent on disturbing the public peace: the May-Day celebrations; the Korean riots in the Kobe-Osaka area; and inflammatory rallies, usually instigated by Communist agitators, involving as high as 50,000 participants.

It was a general policy of SCAP to relax all restrictions progressively, as the Japanese recovered their pace and reform movements became practicable. Under this policy and because of the marked decrease in violations and a concurrent upswing in the number of publications submitted for pre-censorship, press censorship was modified on 6 June 1947.32

Another relaxation of censorship control-the first major one-occurred on 1 August when all Japanese broadcasting stations were transferred to post-censorship, though they were required to submit for pre-censorship questionable material concerning the Allied Powers, and the Occupation or its objectives.33 During the following month a close check on broadcasts revealed that radio stations had taken great pains to conform to the radio code. Only two tenths of 1 percent of the broadcasts were disapproved during the period.34

The second major reduction of censorship took place on 15 October, with the transfer to post-censorship of all book publishers excepting fourteen who specialized in ultra-right and ultra-left material. These continued to be on the pre-censorship list.35

On 15 December came the third relinquishing of censorship control, when 97 percent of all magazines edited, published, and distributed in Japan were placed on post-censorship.36 Again ultra-right and ultra-left publications and those which, because of circulation, subject matter, censorship record, or influence, required closer surveillance were kept on pre-censorship. There were twenty-eight

[239]

magazines in this category.

The fourth major relaxation of censorship control over informational media was effected on 26 July 1948, when all pre-censored news-papers and news services were transferred to post-censorship.37 The pre-censored, indigenous press was transferred to a post-censorship status in four separate increments during the period 15 through 25 July 1948.38

In each of the three major publications fields, some publications were on post-censorship even before these major transfers. In each field, however, the existence of partial pre-censorship controls was an indirect but effective restraint on the post-censored publishers as well. The possibility of being returned to pre-censorship status was sufficient incentive to keep most post-censored publishers in line with the Press Code. When this indirect restraint was largely removed by the major transfers to post-censorship, the effect on the volume of Press Code violations was graphic: the monthly violation rate in newspapers was five times as great, in books, twenty times as great, and in magazines, twice as great as before transfer. The upsurge in magazine violations was less pronounced than in newspapers and books because of the fact that twenty-eight extremist magazines were kept on pre-censorship, whereas 100 percent of the newspapers and books were post-censored.39

On 15 October 1947 twelve publishing firms had been placed on post-censorship with but one proviso: that all books dealing with the Allied Powers, the Occupation or its objectives were still to be pre-censored. On that same date fourteen others had been retained on the complete pre-censorship list. By 30 August 1948, however, these companies were notified that thenceforth all of their publications would be post-censored.40

At the end of the year, magazines, books, prefectural newspapers, broadcasts, and motion pictures were being post-censored. This release from pre-censorship control over the major portion of the Japanese publishing field

[240]

permitted CCD's Press, Pictorial, and Broadcast Division to expand its mission as an intelligence and analysis agency.41

As the facilities and communications surveillance techniques for obtaining information of subversive activities developed, this phase of CCD operations increased in importance until it dominated Communications Division reporting. Surveillance of telephone, telegraph and postal channels yielded a continual flow of "action leads" information to user agencies. Such reporting was concerned with violence, strikes, Communist activities or any other developments which were of a subversive or possible subversive nature. In addition to intelligence of this type, CCD often obtained, chiefly through the monitoring of telephone conversations, valuable advance information on plans for strikes, demonstrations and other activities. These spot reports were forwarded immediately to CIC and other action agencies in time for them to take precautionary measures. Individuals and organizations believed to be of a subversive nature were watch listed by CCD and communications to or from them were carefully studied by personnel trained to detect subversion and clandestine correspondence methods.

In January 1948 communications surveillance reporting of public reaction based on four million intercepts per month was instituted, providing all SCAP agencies with an unbiased, accurate picture of public reaction to the government, to SCAP policies, and to other controversial issues.

Information obtained through censorship was forwarded to SCAP sections or other user agencies in the form of so-called "comment sheets" that were, in fact, substantiated bases for corrective action. An enormous volume of information otherwise unobtainable by user agencies, since they did not maintain field surveillance themselves, was furnished through these comment sheets. (Plate No. 77)

The effect of this type of information was recognized as a direct contribution to the economy of Japan. Many SCAP civil sections benefited from this service and acknowledged its direct monetary or economic values. In a single month, CCD "leads" furnished to ESS disclosed thirty-eight large scale economic violations, leading in turn to the indictment of ninety-three companies and two hundred seventeen persons with a recovery of materials aggregating a value of 101,071,017 yen.42

CCD "watchlist" reports of over a year enabled ESS to recover critical items in illegal market operations to an aggregate amount of 431 million yen; blackmarket value of these goods was estimated at five billion yen.43 Through investigation of one CCD intercept, the Civilian Property Custodian located 16,000 carats of industrial diamonds. Further searching disclosed the location of sufficient diamonds to make the final total 30,000 carats. As a result of only one intercept 52.5 pounds of hoarded platinum, with an official value of 53,679,377 yen, was recovered.44

The 441st Counter Intelligence Corps: The 441st Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC)

[241]

PLATE NO. 77

Comment Sheets Disseminated by CCD to User Agencies:

Comparison between June 1947 and June 1948

[242]

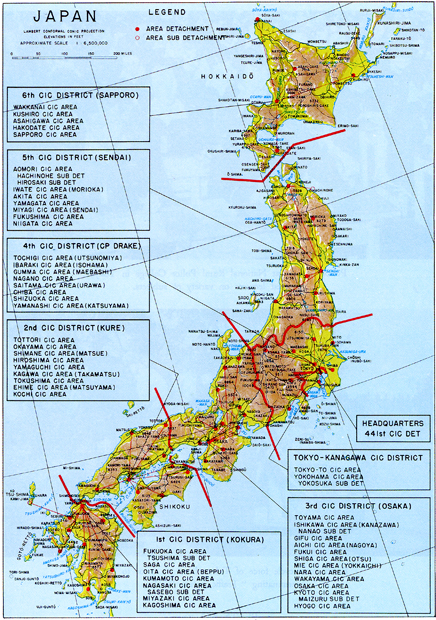

and the 319th Military Intelligence Company (MIS linguist unit) constituted the major investigating agencies in the field pertaining to foreign espionage, sabotage, treason, sedition, subversive activities, security violations or other acts inimical to Occupation objectives. In the field of counter intelligence the surveillance coverage of Japan was uniform through national distribution of field detachments. (Plate No. 78)

Fifty-eight separate Counter Intelligence Corps field detachments were established in localities corresponding to the political, prefectural division of Japan. The 441st CIC was closely coordinated with the Occupation troops: the First CIC region corresponded to the I Corps Area; the Second CIC region, to that of the IX Corps. Six CIC districts coincided with areas assigned to United States divisions and British units. Fifty field units, with seven additional sub-detachments were distributed to cover every important political subdivision of Japan, i. e., the prefecture, the hub of provincial administration.

Reports on activities of field detachments in investigating potentially subversive or other undesirable individuals and organizations were sent to the 441st Headquarters in Tokyo.

Initially the check on enforcement of SCAPIN's was the responsibility of the agency initiating them or the one whose functions were most closely related to their purposes; however, in early 1946 SCAPIN's were developing faster than surveillance agencies could be organized to cope with them. It was during this period that two of the most important SCAPIN's were issued they ordered the abolition of certain ultra-nationalistic organizations and the removal of those office holders whose wartime policies and activities indicated they were unfit to lead Japan along democratic lines.45

Under these "purge directives" CIS, in conjunction with the Government Section, furnished advisory opinion concerning the eligibility of persons to hold public office or a position of responsibility and influence in public or important private enterprise. CIC field teams were soon taking definite action in relation to these SCAPIN's. When informed that a person considered unfit was still holding office, CIC took immediate steps to determine the validity of the allegation, and, if proved, to remove the man from his position.46

On other occasions the activities of certain organizations indicated to CIC agents evidence of doctrines propagated by officially banned groups. Members of a purged organization sometimes joined or created new groups under different names and seemingly different constitutions but with the same old militaristic or supra-nationalistic tendency.47 CIS' connection with the purge directives terminated in

[243]

early 1948. Elsewhere, CIC continued to investigate non-compliance with SCAPIN's but essentially only in the role of a fact-gathering agency.48 To CIC, well deployed in every prefecture in Japan, went the additional and informal responsibility of enforcing the directives of other SOAP agencies until they were ready to function in the field.

Another SCAPIN which absorbed much of CIO's attention in the early days of the Occupation concerned the surrender of arms by the Japanese people.49 This responsibility continued throughout the Occupation in conjunction with troop patrols, and small caches of arms or ammunition were uncovered at irregular intervals.

Following the completion of apprehension of the majority of "Class A" war criminals, the tasks of CIC shifted largely to detection and reporting of subversive activity.50

The CIC Training School, which opened in the Brisbane area in 1943, provided special training in investigative procedures for officers and agents and replaced its "combat courses" with classes pertaining to Japanese social, political, and economic life. Lectures were given by native authorities on political changes in Japan during the war; Japanese court and newspaper systems and methods used by civil and military intelligence, police and secret agencies were studied. An effort was made to concentrate on the practical aspects of CIC activities; great emphasis was laid on the Japanese prefectural and national government structure and means by which CIC could best utilize Japanese investigative facilities.51

Public Safety Division: The organization of a public safety regulatory body was another

[244]

PLATE NO. 78

441st CIC Districts and Field Detachments, 4 October 1948

[245]

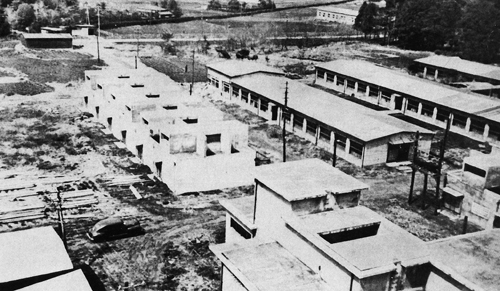

Police trainees at National Rural Police College in Tokyo

attended lectures on variety of subjects.

Entire motorcycle force of Tokyo lined up prior to parade

terminating "Traffic Safety Week".

PLATE NO. 79

Police Training Program, 1948

[246]

task in the field of Occupation control and reform. Japan's pre-Occupation public safety services, developed under purely militaristic control, required new policies and re-education. Since the public safety organs were the only stabilizing forces which would remain in Japan upon the eventual withdrawal of the Occupation forces, the early reorganization and training of these agencies along democratic lines became a prime objective of SCAP. The Japanese pre-war police had been a national organization, directed from Tokyo, with wide powers of surveillance, arrest, and other forms of "protective custody." They were to be stripped of all illegal powers and their procedures were to be consonant with those of police in a democratic state. In order to cover activities which had been under the police, such as fire defense and fire prevention, wholly new organizations would have to be developed. The prison field, regarded chiefly as a money making organization, was to be brought into line with western standards and given a reform emphasis. The Japanese people, defeated in war, with their cities burned, their factories demolished, their economy bursting out of control, were in a difficult position. They lacked food, clothing and shelter, the basic necessities of life. National unrest developed quickly due in part to uncertainty as to Occupation attitudes and activities, but more to the disruptive activities of the discordant elements, including many recently released political prisoners.

Since the field of public safety was unexplored and not too closely related to previous assignments of CIS, it was necessary to build a Public Safety Division from the ground up. A skeleton staff was immediately appointed with In the CIS administrative office, but the Public Safety Division (PSD) did not begin operating until early 1946.52

At that time CIS introduced experts in the public safety field from the United States to advise on the reform of corresponding Japanese organizations. Under the guidance of these specialists, the Public Safety Division supervised the reorganization of the Japanese police, fire fighting, and prison systems. In attempting to establish modern democratic organizations in these fields, it was necessary that the status of Japan's shattered economy be kept in mind while adequate measures were being provided to permit future realization of ultimate objectives as the level of Japan's economy was raised.53

On the basis of numerous suggestions by Police Branch, PSD, the Japanese Government submitted a master plan of police reform. All municipalities of 5,000 or more population were to have autonomous police departments. These were to be directed by municipally elected Public Safety Commissions. A few more than 1,600 cities fell in this population group, and 95,000 municipal policemen would serve. It was planned to police the non-urban areas of Japan with a national rural police force of 30,000. A National Public Safety Commission, appointed by the Prime Minister, would be charged with establishing policies and plans for the national force. This plan, ap-

[247]

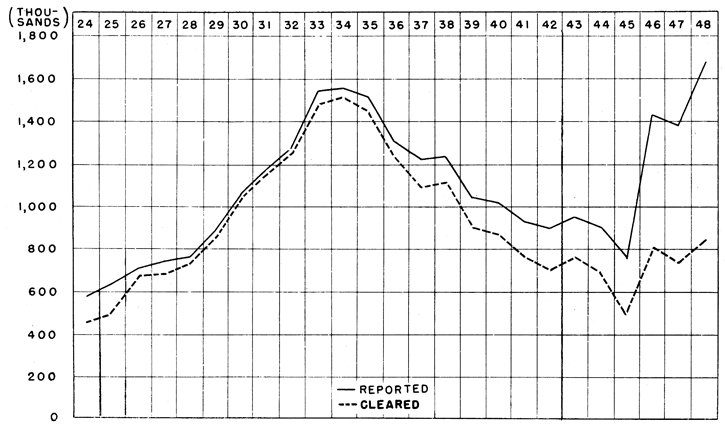

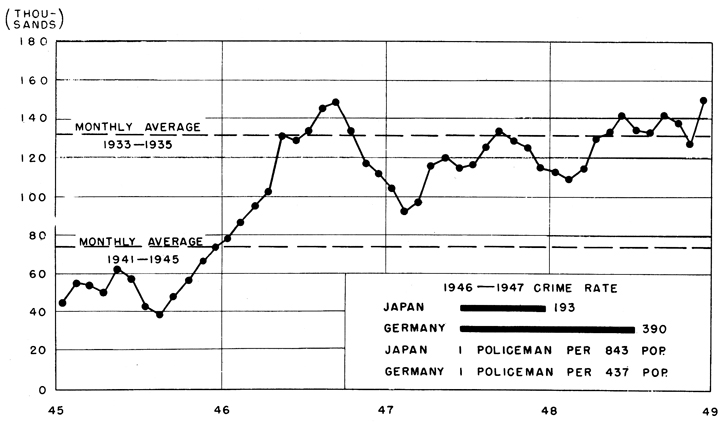

Offenses Reported and Cleared: 1924-1948

Offenses against the Criminal Code: 1945-1948

PLATE NO. 80

Crime Statistics and Police Effectiveness: 1924-1948

[248]

proved in principle by SCAP, was passed by the Diet in December 1947.

Now no longer under police control, the fire prevention agencies were necessarily re-grouped. Japan's fire losses, Fire Branch discovered, were largely due to the combination of closely spaced houses along narrow streets, the constant use of open fires and carelessness in handling them, and meager equipment for fire-fighting coupled with a lack of "know-how" among the thousands of volunteer fire fighters. Whenever conditions indicated that municipalities had ability to support a paid fire department, they were authorized to have them. These, like the local police, were under the local Public Safety Commissions; while on the national level the Fire Research Institute was under the national commission. Within one year of the opening of the first police school nearly 80,000 recruits had been given basic training in American methods as adapted to Japanese needs.54 A series of schools followed: they continued to train the police in the powers, limitations, and responsibilities of law enforcement, oriented newly created prefectural and municipal Public Safety Commissions in their functions, and taught the Japanese people to consider the police as a safeguard of liberties and civil rights.55

Japan had never had a really excessive crime rate, although the middle thirties saw Japan's highest pre-war rate with an average of 130,000 offenses per month. The effectiveness of the wartime police reduced crime to the lowest recorded in police history: the 1941-45 average showed only 75,000 offenses per month. With the end of the war, the inherent unrest of a defeated people, the lack of adequate food, clothing and housing, and the return of millions of demobilized personnel, crime took an upward swing until it exceeded the high figure of the thirties. (Plate No. 80) This increase in crime required constant surveillance by the Public Safety Division.

Studies were made of police communications systems, police training, metropolitan police, and rural police. Along with its research work, the Division conducted numerous widespread investigations throughout Japan.56 Inspections and surveys of public safety organizations

[249]

|

|

|

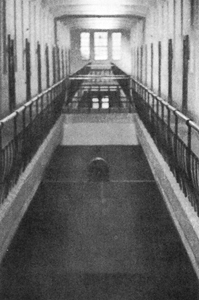

Cell blocks made spotlessly clean and kept sanitary. |

Kitchen made sanitary and food improved in amount and quality. |

|

|

||

|

|

|

Prison industries revitalized and expanded |

All prisoners made to learn and do useful work. |

PLATE NO. 81

Fuchu Prison, Tokyo: Improvements Made, 1945-1947

[250]

were constant.57 Many corrections were made on the spot, merely by supplying helpful suggestions. Almost all the police detention cells in Tokyo were rebuilt and modernized in this manner. Police brutality and corruption were curtailed and Japanese police inspectors were trained to continue the new program on their own initiative.

By thoroughly investigating the Japanese prison and reformatory systems, experts in penology were able to gain first-hand information of every important penal institution. The Ministry of justice was abolished and the Attorney General took over the approved duties, but the change carried little of new import for the prisons. There was no change from national to local control but something far more difficult-a change in the prison and reformatory functions without a corresponding change in basic authority. Japanese prisons had been interested in making as much money as possible, thus keeping operating expenses at a minimum. Under the direct guidance and supervision of former American prison wardens, Fuchu and Yokohama Prisons became pilot plants to demonstrate American principles of operation. Again, it was possible to make many corrections on the spot with follow-up investigations to insure that suggestions were carried out. Several special projects were based on information thus obtained: guard training schools, prison industries, paroles and probation practices, and prisoner classification. After establishment of the Public Safety Division, the prisoner mortality rate in Japan declined sharply.58

Studies of Japanese public safety laws and regulations made by the Legal Branch, resulted in recommendations for changes in criminal and juvenile codes, jury laws, rules of evidence, criminal defense and prosecution procedures, and other legal aspects of public safety.

Equally effective work was accomplished in the other branches of the Division. The Fire Branch extended its investigations into every major city of Japan. A system of local autonomous fire departments was set up. Local units were gradually reorganized along functional lines, using the modernized Tokyo Fire Department as a model. A Fire Research Institute was established. Other problems encountered by this Branch included training in fire defense and in fire prevention, development of plans for disaster control, and long-range municipal planning to minimize damage from catastrophes.59

Great effort was made to improve the working conditions of the firemen, to remove them from the control of the police bureaucracy, and give them the basic fire fighting equipment. Detailed city grading studies were begun, based on the standard American fire underwriter's procedures. Deficiencies were brought to light in this way, and insurance rates were equalized.

[251]

Japan's Fire Research Institute, April 1948, formerly the Japanese

Central Aeronautics Research Institute.

Ickikawa Fire Department is inspected by PSD Fire Branch, March 1947.

PLATE NO. 82

Fire Prevention

[252]

PLATE NO. 83

Relationship of Counter Intelligence, Civil Censorship, Military Police and

Military Government Detachments, 15 December 1948

[253]

By means of an elaborate publicity campaign during Japan's first "Fire Prevention Week" a great deal of cooperation was obtained from prominent citizens; neighborhood fire protection associations which gave valuable service in eliminating local fire hazards were formed.

Japan's geographical condition as a group of islands pointed to yet another phase of public safety, the maritime. Here the national control was weaker and jurisdiction over harbors was largely of a local character. Guided by PSD suggestions, the Japanese set up a Maritime Safety Board with functions similar to the American Coast Guard Service. A Maritime Training Institute was planned to supplement the seamen's training and the reconstruction of the nation's war-wrecked navigational aids system was given high priority.

The Maritime Safety Branch was primarily interested in the establishment of a Japanese Maritime Safety Service (Coast Guard) and made recommendations relative to navigational aids, sea-rescue, hazards to navigation, and prevention of illegal entry and smuggling.60

Security Surveillance and

Law Enforcement

The initial and continuous tranquility of Japan, compared with other world areas, has perhaps been the outstanding success of the Occupation. This was primarily due to accurate counter intelligence information on every shade of public unrest-in the field of labor, in communist infiltration, and in movements of disillusioned, repatriated military personnel.

Certain law enforcement and surveillance agencies in the field maintained potential observation posts in affected areas, although their employment, missions and duties differed. From an intelligence point of view, the political, administrative and economic reporting of Military Government teams served to supplement and confirm CIC field reports and gave GHQ a factual picture of current activities. Both agencies continued to be deeply concerned with the maintenance of local law and order.

There was also inferential relationship between the Counter Intelligence Corps and the Criminal Investigation Division (CID) of the Provost Marshal (PM). Important leads for the PM/CID investigation of blackmarket movements, for example, came from CCD and CIC. The primary mission of the Provost Marshal however, continued to be that of troop control, while CIC was principally concerned with subversive acts by Japanese or foreigners inimical to the Occupation forces or the policies of SCAR The Military Police and CID (PM) handled police cases as they related to the U. S. Army personnel: vehicle traffic, off duty discipline, theft, and miscellaneous criminal charges. Counter Intelligence concern with United States troops and civilians was largely limited to questions of security, i. e., disaffection, disloyalty, and subversion. CID however, inevitably overlapped CIC investigative processes.

In a survey of the relative density and distribution of surveillance agencies (Plate No. 83) the concentration of Military police and Criminal Investigation Division strength naturally coincided with major troop distribution, the Tokyo, Yokohama and Osaka areas being heavily covered. As regards relative density, Military Police and CID maintained twenty-five units in only twenty-four prefectures, while the 441st CIC manned sixty posts in forty-six prefectures, a complete national coverage.61

[254]

The Military Government teams more nearly approximated the prefectural distribution of the 441st CIC throughout. Their purposes and capacities were closely related to CIC surveillance in the same areas. Although "Blacklist" anticipated "combined operations" of these two agencies, they were never officially effected, but in practice CIC and MG units in the field cooperated closely.62

A major turning point in the development of the section occurred in May 1946 when it was placed under direct control of the theater G-2, thus eliminating the artificial staff division between counterintelligence and operational theater intelligence which had been considered a wartime weakness.63

Since the Government Section had final authority over questions regarding compliance with terms of the purge directives, the selective check had assumed such proportions as to make proper enforcement impossible for so small a unit as G/A Branch; this responsibility was transferred from CIS to Government Section on 11 January 1947.64 Except for the continued filing of questionnaires in CIS for intelligence purposes, CIS was no longer concerned with enforcement of the purge directives.

A new element made itself felt in this period: loyalty checks on personnel working for or with the Occupation. The Loyalty Desk was established in June 1947 at a time when Washington, apprehensive of Communist infiltration into Government offices, required a thorough security investigation of all Army employees.65 Two other special categories of security checks covered persons traveling in the FEC and certain aliens wishing to marry American Occupation personnel. The primary purpose of investigation in both cases was counterespionage.

The Loyalty Desk served other staff sections in numerous ways. It made record checks of proposed entrants for Civil Information and Education Section, appointees holding power of attorney for the Civil Property Custodian, and Japanese witnesses and lawyers required by the Legal Section to participate in war crimes trials held outside Japan. At G-1's request, checks were initiated on individual Japanese who desired to return home, and various other staff sections turned

[255]

to CIS for clearances of foreign nationals to handle classified information.66

The forces working against democracy were not all of foreign extraction. The pattern of Communist thinking was obvious enough, but the job of detecting it in individual cases was difficult. To establish enough positive evidence to take action against disaffected Americans in the Far East Command called for skillful and painstaking investigations.

The Domestic Subversion Desk was a control group which followed up G-2's interest in the arrest, transfer and/or release of war criminals, and in addition handled many types of cases (other than leftist) involving willful activity to undermine the interests of the United States. Illustrative is the following list of typical cases acted upon by the Subversion Desk during 1947: alleged American traitors; impersonation of CIC agents by Japanese and foreign nationals; Japanese underground movements; German intelligence activities in the Far East; requests for information from Allied Missions; information about "Tokyo Rose"; possible arson of Occupation forces installations; information on Japanese war criminals; investigation of hidden arms and ammunition; ultra-nationalistic, anti-Occupation activities; Army postal violations; information on hidden goods; information for trial of alleged war criminals in the United States; and military script conversion violations.67

The Compilations Branch included the Organizations, Personalities, Foreign, and Microfile Sections. Its role was that of a specialized information collection agency, with access to original Japanese documents, direct contact with innumerable Japanese persons, and a highly developed dissemination system geared to furnish operational information to other branches of Operations Division. Through continued liaison with CIC and the Document Section of ATIS, and through cultivation of

[256]

independent Japanese sources not generally or easily available to other less specialized groups, Compilations Branch built up a Japanese National Reference Library which was recognized as an authoritative source for original Japanese documentary material. Among its materials were thousands of personality and organization dossiers, an extensive microfilm index of Special Higher Police cards, and a large card file of higher Japanese Civil Service officials.

The Microfile Section recorded thousands of documents for other sections of CIS as well as for the Japanese National Reference Library. It included among its files the records of all cases pertaining to violations of the Peace Preservation and the Military Security Laws, the Saionji-Harada Memoirs (some 3,000 typewritten pages), the Marquis Kido Diary, and innumerable documents of counter intelligence interest.

Publications Section, as its name implies, was concerned primarily with the preparation of CIS' contribution to various G-2 publications. Its chief project, the "Periodical Summary," developed from the weekly "Situation Report Japan" which was first published on 4 November 1945, and which after three issues became "Occupational Trends Japan and Korea." Designed as "a compilation of Japanese trends in political, educational, psychological, and religious spheres, as gathered from reports submitted by counter intelligence agencies," the publication presented to theater commanders and to the War Department a full picture of the civil side of occupation intelligence.

In addition to the "Periodical Summary" the Publications Section compiled the counter intelligence part of the G-2 Daily Intelligence Summary and contributed to the operations report for the War Department.

Special Projects Section was under direct control of the commanding officer of 441st CIC Detachment. To meet the international aspect of counter intelligence, Special Projects sub-sections were established in every CIC area in Japan.68 The Section headquarters concentrated on cases concerning espionage, foreign inspired sabotage, and radical or foreign inspired subversion.

Organized labor, a force which, due to the machinations of left-wing leaders, at times threatened to defeat the liberal Occupation directives that had brought it into existence in Japan, was observed by the Labor Branch of Special Projects Section. This unit furnished considerable information to the Labor Division of SCAP's Economic and Scientific Section, as illustrated by the timely and continuous reports provided prior to the incipient but dangerous general labor strike in February 1 947 and a similar disturbance planned by subversive elements in October of that year.69 It was also responsible for notifying CIC field units of expected developments in the labor arena. It received reports from the field teams in case of strikes, important labor gatherings, the reaction of local labor organizations to speeches by prominent Communists, and other similar events.

Under the new freedoms granted to them by SOAP, the Japanese people rushed to organize in the political and labor fields to a degree that was bewildering to Western observers. With a hereditary talent for banding

[257]

together, Japanese from all walks of life took advantage of their freedom from the militaristic state domination which had guided them for centuries and the number of societies, parties, clubs, and leagues representing every shade of opinion grew without check. They held meetings, parades, and demonstrations to give vent to their feelings, whether on political matters or for the purpose of winning public support for higher wages. This development in the early months of 1946 was widespread and rapid; it soon became apparent that unless some method of keeping track of such events was established, there would be frequent opportunities for local troublemakers to circumvent the objectives of the Occupation. It was at this time, too, that under Communist prompting, organized labor was beginning its first major wave of strikes. To offset this situation, the use of "spot reports" was initiated to cover all unusual occurrences throughout Japan.70

Such incidents were defined to include any event which showed indications of actual or potential sabotage, treason, or other matters of CIC interest; fires, explosions, epidemics, earthquakes, or other accidents which might affect the Occupation effort; strikes, mass demonstrations, or misconduct of Occupation or Japanese personnel; and miscellaneous events such as attempts at assassination, attacks on the Japanese Government, and incidents precipitated by or indicating foreign interests. All such happenings were promptly reported to the 441st Headquarters.71 For outlying areas the telephone presented the fastest mode of communication but, for incidents which occurred in the proximity of GHQ, mobile radio equipment was often used by CIC.

Early in 1947 arrangements were made to utilize the Eighth Army teletype network for CIC spot reports on a twenty-four hour basis. By 15 March spot reports were flowing into 441st Headquarters via teletype, radio, and telephone in a steady stream. In that month alone, 113 CIC spot reports were sent to CIS to be forwarded to the AC of S, G-2.72

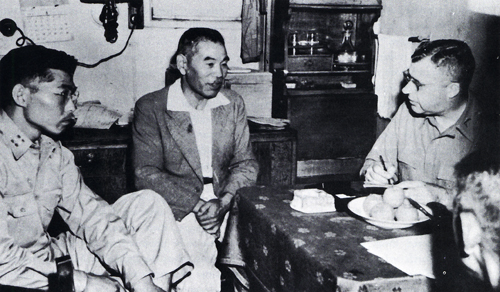

Both operational and counter intelligence agencies were interested in the interrogation of returning PW's.73 In November 1946 the counter intelligence coverage of this field was begun. Although certain ports were designated as repatriation centers through which all internees entered Japan, the varied destinations of repatriates in Japan necessitated coordination of all CIC field units in handling this problem.74

In the 441st CIC Headquarters, a special Repatriate Branch was established within the Special Projects Section to coordinate the operations of the field units. The over-all plan entailed a three-step system of screening incoming repatriates. In the initial phase, all returnees, while still aboard ship, completed forms concerning their original address in Japan, full name, age, place of confinement, and intended place of residence following the completion of repatriation. The forms also asked for information concerning activities in the Japanese Army and later within the prison camp, indicating political affiliations, social activities, and indoctrination. By screening

[258]

Interrogation officers check passenger list with captain of the

Tokuga Maru.

Repatriates are given instructions on how to fill out repatriation forms.

PLATE NO. 84

Repatriation Interrogations, August 1948

[259]

these forms, it was possible to establish which repatriates were of immediate counterintelligence interest. These were interrogated at the port in coordination with Eighth Army intelligence officers, constituting the second phase in the plan. Japanese nationals were used to carry on much of the interrogation and routine work not involving classified information. CIC coverage of port customs check stations was maintained. The third phase included intensive interrogation by Allied Translator and Interpreter Section (ATIS) in Tokyo of those suspected of possessing sensitive information.75

Data from the personal history forms was transcribed on cards in English. A card file of repatriates was set up with master file by CIS Operations Division while files pertaining to repatriates in each CIC area were established in the CIC area office concerned.

As the number of repatriates continued to grow, a priority system for classifying them was adopted, to show those who merited intense interrogation without delay, those of counterintelligence importance who did not require immediate questioning, and those who were given a routine check within a designated time. Complete statistical data was kept on them and submitted monthly to 441st Headquarters, CIS, and G-2.76

In an effort to lighten the work load of personnel in the field, CIC operations at the repatriation ports were expanded and improved. More efficient interrogations were accomplished before the repatriates had a chance to begin their trek home.77

One of CIS' problems in Japan centered in the Korean minority.78 A If they chose to remain in the country, they were expected to conform to Japanese laws and to receive equal treatment with Japanese citizens. The Koreans, however, in a surge of revulsion against their former oppressors, interpreted their liberation as meaning complete freedom from Japanese- imposed restraints of any kind. This at-

[260]

Japanese shipmaster of vessel returning repatriates to Japan, is

interrogated regarding number of passengers aboard.

Repatriates are interrogated by members of the Home Ministry aboard

the Tokugu Maru at Hakodate, the initial processing phase.

PLATE NO. 85

Repatriation Interrogations, August 1948

[261]

titude of defiance led to recurring conflicts with Japanese authorities and in 1947 the rate of crime for Koreans was almost three times that for Japanese.79

Under a voluntary repatriation program initiated in March 1946,80 more than 1,100,000 Koreans were repatriated. In March 1947 there were 542,139 registered Koreans remaining in Japan, constituting the largest minority group in the country.81 Korean groups became increasingly restive and their numbers expanded through illegal entries.82

Although police apprehended 21,000 illegal entrants between April 1946 and January 1947, it was believed that those who evaded the patrols and successfully entered Japan greatly outnumbered those who were caught. Between March 1947 and March 1948 the registered Korean population actually increased by 10 percent.83

The most serious effect of unlawful entry aside from possible infiltration of agents or agitators into Japan was severe social and economic disruption. Most Koreans returned illegally had no assurance of a livelihood. Local Korean communities managed to circumvent the police by absorbing them speedily and by undertaking illicit activities to prevent their detection. To obtain the necessities of life, the illegal entrants procured unauthorized ration cards.84 Living under assumed names and continually changing residence, this group constituted a prominent factor in disorder and lawlessness in Japan.

The pronounced nationalism developed by the long-oppressed Koreans made them over-zealous of anything Korean: their national language, their culture, and their temples were to be preserved by any possible means. Thus, when the Education Ministry issued a series of directives designed to attain uniform educational standards, the Koreans refused to admit that their schools which were not government subsidized should be affected.85 The

[262]

resultant demand for "racial autonomy" in education (i.e., approval of the use of Korean as the spoken language in the schools, continuance of the use of Korean textbooks, and placing of the schools under Korean management and supervision) precipitated one of the most serious outbreaks of violence during the Occupation.86

More than ninety Korean organizations came into existence following the surrender of Japan. The major organization, "League of Koreans Residing in Japan," ostensibly represented a consolidation of the aims of the many former groups to form a strong lobbying bloc to further interests of Korean residents in Japan; the leftist nature of the League, however, was manifest almost from the first. When, through intrigue and intimidation, the minority communist faction gained control, a rightist group broke away from the League and formed the "Youth Organization for the Reconstruction of Korea" (Kensei).

In February 1946 the adult members in the Kensei formed a separate organization known, after a series of mergers and name changes, as the "Union of Great Korean Republics Residing in Japan" (better known under a former name, "Korean Residents' Union" or the Mindan). With a few exceptions the two rightist groups worked together in their pursuit of a mutual goal-foundation and recognition of a rightist government in Korea. Despite their efforts the rightist elements never reached the strength and power of the leftist groups in Japan. Meanwhile, leaders of the Japan Communist Party took note of the leftist trend of the League and promptly took steps to bring it into the communist sphere of influence.

The close relationship of the leftist Korean groups in Japan with the Japan Communist Party is well illustrated by the fact that some of the top leaders held positions in both. In joint movements, these groups were mutually supporting, each supplying certain essential elements for protest movements. The Koreans furnished enthusiastic mobs, pickets, and strong propaganda.

Subsequent to the termination of the war, Korean education was chiefly concerned with the teaching of the Korean language. Since the prospect of their remaining in Japan assumed a semi-permanent aspect and since their schools might be suppressed if nothing else was taught, formal revisions were made in the education policy to include subjects normally taught in Japanese schools.

Seventy-two Korean news agencies, newspapers and magazines disseminated news and information to the Korean people in Japan. In addition, the leftist Koreans utilized other media of propaganda, from the Kami-Shibai

[263]

(picture stories for children) to nationwide poster campaigns. One of the most powerful and economical propaganda vehicles was rumor spreading, in which the Korean leaders excelled and to which the average Korean was extremely susceptible.

The greatest single political group as a medium of potential trouble for the Occupation was the Japan Communist Party (JCP), with its varied and persistent attempts to discredit and nullify the program of democratization. From the outset, it was recognized that this group's activities and methods made it less a political party and more a fifth column introducing alien ideologies into Japan. This factor became a prime concern of Counter Intelligence.87

Early in the Occupation, it was realized that the release of all political prisoners, a completely laudable political gesture, was also opening the doors to a group of well-trained, fully indoctrinated obstructionists. The Communists were quick to reorganize their Party and to start its program of anti-democratic activities, which sometimes found unexpected support from disorganized sections of the post surrender population.

As in every other non-Communist country, the Party in Japan proved to be a menace to all duly constituted authority. Its members, imbued with the philosophy that any means are justifiable as long as they promote the Party's aims, continually resorted to illegal, subversive, and undercover methods to attain their ends.

The JCP devoted its well-correlated energies to interfering with the vital food production, shipbuilding, merchant shipping, democratic organization of labor, and the collection of taxes-to name a few of the methods by which it maneuvered stumbling blocks in the path of Japan's democratization. It sponsored or took over many "front" organizations and put on a comprehensive propaganda program designed to create spiritual confusion among the populace and to promote an alien ideology.

In spite of the essentially conservative character of the Japanese people, the JCP achieved a relative degree of success in penetrating the higher echelons of organized labor during the first two and one-half years of the Occupation. Capitalizing on the confusion and readjustment which characterized the first postwar months, the Communist Party, repeating its tried methods of operation, infiltrated the countless labor unions which were springing up all over Japan as a part of the new democratization program.

The radical complexion of the National Congress of Industrial Unions (NCIU) and its wide control of the workers in Japan's key industries made it a major target for CIS as its activities became more and more openly threatening to the Occupation's goals. Communist infiltration had reached such proportions by August 1946 that the Party's Central Committee was able to instruct the Communist Party faction in the NCIU to incite the member unions to plan a general strike on 15 September 1946, coordinated with a threatened twenty-four hour strike of government railway workers.88

CIS, alerted by CIC and CCD reports,

[264]

watched this activity closely. Enough information had been correlated and forwarded by CIS' Special Activities Branch preceding the intended date of the strike to enable GHQ to know exactly what to expect and to plan accordingly.89

Following labor's futile attempt at a general strike in the fall of 1946, the Communist Party files in CIS expanded by leaps and bounds. Data continued to flow in from networks of informants. The NCIU by now was definitely established as being the instrument through which the JCP attempted strikes.90 Through extensive G-2 reports, ESS and other staff sections were apprised of the fact that the NCIU contained many labor unions in a large number of vital industries, (e.g., coal, steel, communications, newspaper and radio, publishing and printing, and electric power as well as such local unions as the Tokyo Area Government Railway Workers Union, which was thoroughly impregnated with Communists.91

The Civil Intelligence Section kept day by day progress studies of the NCIU and its Communist-dominated organizations. "Spot" reports were a valuable source of current information, often being forwarded to General Headquarters within a few hours after facts were uncovered by CIC investigators.

The Party's influence was tested in the fall and winter of 1947 when the Japanese Government, recognizing a tendency of farmers to withhold their crops from regular rationing channels for high blackmarket prices, set rice quotas for all prefectures to fill. The Communists, in attacking this form of regulation, hoped to bring discredit upon the methods as well as the personnel of the Japanese Government, meanwhile furthering the Party's cause among farmers. In essence, the program took the form of encouraging farmers to hold back as much of their required rice production quota as possible. At the same time, in metropolitan areas, Communists pointed out that the Government was unable effectively to carry out its rice ration distribution program despite the constant threat of hunger to city workers.92 In addition to obstructing the delivery of rice, the JCP also advocated that the farmers refuse to buy land from the Japanese Government, while at the same time in Tokyo they were agitating that the government sale of land to farmers had been a complete failure.

While not of threatening proportions, the Communist Party and its operations brought into sharp relief the security problem of the Occupation. The docility of the Japanese since war's end was encouraging, but the infiltration of foreign ideologies could not be discounted. As long as Occupation troops were available, the relative weakness of the new governmental structure was not apparent, nor would it be seriously tested. There was no question that the process of democratization was well under way, but there were certain factors that could not be ignored: the deterioration in national economy, the rising spiral of inflation, the increasing importance of the labor movement, the unrest in disaffected groups, and Communist penetration.

Communist Infiltration of Repatriates

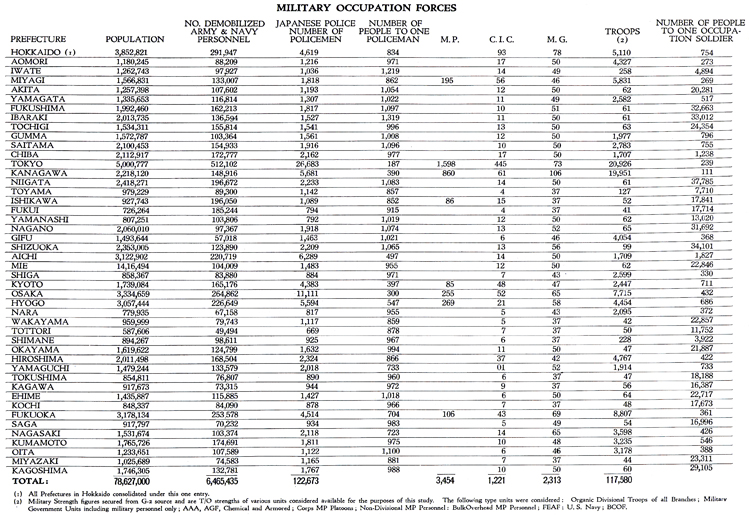

The decrease of Occupation troops in Japan represented a steadily mounting internal security risk. As of the end of 1948 the total strength was, set at 117,580 of which only 68 percent were combat troops available for emer-

[265]

PLATE NO. 86

Analysis of Population, Military and Police Strength by Prefecture 15 December 1948

[266]

gencies. This force, plus a poorly equipped Japanese police force of 122,673 men, constituted the control force for almost 80 million people. (Plate No. 86)

Military Police and Counter Intelligence units were scattered so thoroughly throughout Japan that their numbers in any given area would have been insignificant in an emergency. However, they were in a position to furnish first warning of impending disturbance and to supply information to tactical troops dispatched to the areas.

Each prefecture in Japan contained a Military Government team. These units could have provided guidance and liaison, but would have been of no value tactically.

The British Commonwealth Occupation Force controlled nine prefectures on Shikoku and southern Honshu. BCOF was supplemented in its area by the Military Government teams, and counterintelligence functions were implemented by U. S. personnel. During 1948 the strength of BCOF troops had been reduced by about 70 percent, leaving some 4,600 officers and men of the Royal Australian Army to handle the principal Occupation activities in Hiroshima Prefecture. There were also 850 representatives of the Royal Australian Air Force, 200 of the Royal New Zealand Air Force, and 140 of the Royal New Zealand Army based in Yamaguchi Prefecture.93

By placing density of population figures against Occupation strengths, the ratio of repatriates to troops and police becomes significant.

Repatriates had become a target for the Communist Party. While there had been no incidents, no action of defiance in the past, the general demobilization and the progressive return of millions of jobless soldiers introduced a potential security problem.

There were five areas in Japan in which there were particularly heavy concentrations of repatriates and which were therefore critical areas from a security standpoint. Note the ratio of demobilized personnel to population density. Osaka, typical of this general situation, as of 31 December 1948 had:

| Returned navy personnel | 83,423 |

| Returned army personnel | 181,439 |

| Total prefectural population | 3,334,659 |

| Japanese police | 11,111 |

| FEC troops | 7,715 |

The significance of these over-all statistics is in the ratio of police and the population density: one Japanese police to 300 population, and one Occupation soldier to 1,000 population. It is obvious that this insignificant ratio of Occupation personnel of one to 432 immediately available FEC troops in a critical area could hardly prevail against a restless population of over 3,000,000 with a highly trained 10 percent nucleus of military repatriates to furnish organized leadership.

On a national basis, at the end of 1948, similar ratios existed:

| 1 U.S. soldier per | 670 population |

| 1 Japanese policemen per | 640 population |

| 1 Military Police per | 22,800 population |

| 1 CIC operator per | 64,400 population |

These ratios were insufficient to counter a serious public disturbance or an aggressive fifth column.

[267]

Go to

Last updated 11 December 2006 |